My Favorite Superfund Site’s Superfailure?

Goose Lake is a Superfund site in Shelton, Washington. It hasn’t been cleaned up 35 years after the Department of Ecology first assessed the site.

A view of Goose Lake.

May 8, 2024

Story and Photos by Maisie Gill

Imagine your favorite green space. A place on the outskirts of town that has it all: plentiful wetlands, thriving native plants and berries, a beautiful lake, and a vast trail network. Truly a perfect space to spend your time, except for one thing. Every time it rains, you smell an overwhelming chemical odor. Would you be concerned? Enough to look into it? Well, in 2020, this became my reality, and I did investigate it because it sounded familiar.

This strange smell reminded me of anecdotes from the first Superfund site. Love Canal, New York, was a town established on top of a toxic waste dump unbeknownst to residents, resulting in exposure to extremely hazardous chemicals, and the smell after rain was one of the first signs noticed according to the New York Department of Public Health. As a result of community pressure to investigate these suspicions, the Superfund program was established in 1980. The EPA allocated funds to identify and clean up sites like Love Canal .

While it sounds conspiratorial to suspect your favorite green space to resemble one of the worst toxic waste sites in American history because of a strange smell, it turns out Goose Lake is a Superfund site designated by the Washington State Department of Ecology (Ecology). It actually resembles Love Canal in many ways.

Goose Lake was historically a hazardous waste dumping site, where it served as the waste sulphite liquor lagoon for the Rayonier Pulp Mills in Shelton, Washington through the first half of the 20th century.

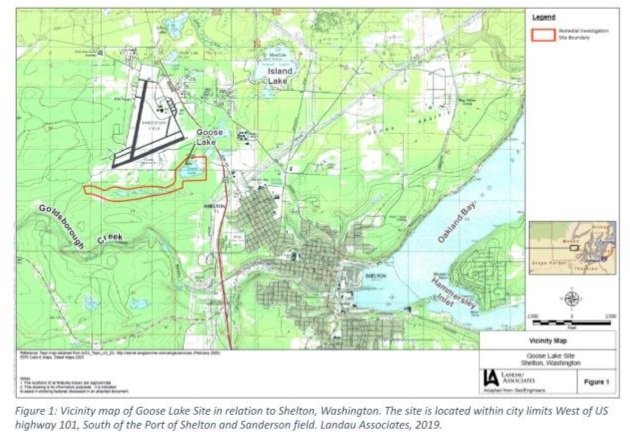

Vicinity map of Goose Lake site in relation to Shelton, Washington. The site is located within city limits west of US Highway 101, South of the Port of Shelton and Sanderson Field.

Goose Lake differs from Love Canal in several ways, however. At least 300,000 tons of waste liquor, which is the effluent generated by wood pulp digestion, was deposited in the Goose Lake site. The makeup of this waste liquor is unknown in this specific circumstance as the chemicals used were undocumented and often experimental, but suffice to say, the chemical components were highly concentrated chemicals meant to break down wood pulp. Over 14 times the total amount of waste dumped at Love Canal was disposed of at the Goose Lake site. Despite this, 35 years have passed since Ecology first assessed the site. Yet, there still is no plan for remediation.

The turnover from discovery to cleanup action at Love Canal was less than five years. But at Goose Lake, 35 years passed since its discovery and there is no cleanup plan yet. In fact, Goose Lake is only at stage four out of nine in the Model Toxics Control Act (MTCA) process.

Model Toxics Control Act process: Goose Lake progress

We are not making enough progress on Goose Lake’s cleanup because the degradation of policy principles has defunded and delayed cleanup activities. This happened first to Superfund and more recently to MTCA, resulting in toxic sites nationwide languishing without funds to be cleaned.

At this point, cleanup programs like Superfund and MTCA may not be capable of preventing another Love Canal. Goose Lake only narrowly avoided that fate after the site was acquired by California-based Hall Equities Group in 2006 to be made into a mixed-use development. When Shelton community members showed up to city council to protest the development in 2014, their concerns fell on deaf ears and the council approved it. In 2017, however, Hall Equities confirmed community suspicions by backing out of Ecology cleanup agreements. The only reason development was canceled was due to the high costs of new infrastructure requirements.

If it weren’t for those requirements, Hall Equities likely would have continued to ignore Ecology regulations, downplay the dangers of the site, and develop a new Love Canal. While development was canceled this time, Shelton may not be so lucky in the future. This near miss demonstrates the need for timelier cleanup activities. Unfortunately, these programs have been deprioritized and defunded to the point where sites sit derelict.

Superfund: Polluter Pays?

Superfunds, while neglected now, had promising origins. The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) was passed in 1980 following public pressure from high-profile toxic waste disasters such as Love Canal and the Valley of the Drums. Superfund is governed under this policy as the primary cleanup program trust fund. Federal funds are necessary in instances of “orphan sites.” These are sites without identifiable Potentially Responsible Persons (PRPs) to assume costs of cleanup. This exercises what is known as the “polluter pays” principle, in which Superfund’s goal is to make responsible parties pay for cleanup work, according to the EPA.

Super(de)fund

Superfund was not always underfunded. Initially, revenue for Superfund’s cleanup activities was generated through two main routes: PRP’s and excise taxes. Excise taxes were on substances thought to contribute to chemical pollution, like petrochemicals. Taxes were expanded with the 1986 Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA). Environmental taxes were introduced on corporations and expanded the tax base from $1.6 billion to $8.5 billion. Revenue generated by these taxes put the “super” in the “fund.” Ultimately, the excise tax was unauthorized in 1995 and stayed that way until it was revived in 2022. With excise taxes out of the picture, Superfund was financed with general taxes and Congressional appropriations.

Principle Degradation

Superfund’s excise tax non-reauthorization represents an “enabling myth” of Superfund. They continued. Despite polluters no longer being taxed, “polluter pays” as a principle remains, becoming more symbolic than functional. As a myth, “polluter pays” obscures the shift towards an increasing burden on taxpayers and away from the original intent of the principle.

Degradation of “polluter pays” through excise tax elimination severely hindered Superfund cleanup. Because it remained as an enabling myth, Superfund’s dwindling funds went unnoticed as program appropriations also declined. Budgets fell 95% from 1997 to 2020 from an appropriately super $4.7 billion to a miniscule $225 million. To put this in perspective, federally funded sites completed before 2008 cost an average of $51 million in 2020 dollars. This is nearly one quarter of the 2020 budget.

Expectedly, Superfund has not been able to succeed on such a budget. In their 2021 report Superfund Underfunded, Jillian Gordner reported FY 2020 was among Superfund’s least productive years on record. Compared to yearly averages from 1983-2019, less than half as many remedial actions were taken, less than two thirds as many National Priority List (NPL) construction projects were completed, and over three times as many partial deletions of sites were made. Superfund cleanup activities are stagnating, according to a 2015 report from the Government Accountability Office. Superfund’s inaction is due to funding declines from tax cuts.

Hands in the MTCA Cookie Jar

In Washington state, authority on toxics policy is delegated from EPA to ECY. Passed in 1988 as a citizen’s initiative, MTCA was modeled after Superfund and has a similar taxation process. While MTCA did not suffer the same excise tax fate as Superfund, it is no stranger to defunding. MTCA’s Hazardous Substance Tax (HST) raises revenue through taxes on wholesale values of petrochemicals. This caused HST revenues to be vulnerable to price fluctuations of petrochemicals. But, it generated a lot of money when oil prices rose in 2008.

Simultaneously, as MTCA’s fund was growing, 2008’s financial crisis was straining ECY. To plug shortfalls and pay ECY employees, the legislature would divert money out of MTCA accounts. This precedent continued long after the Great Recession. From 2007-2015, ECY funding from general tax revenues shrank by 53%. Yet, ECY’s funding from MTCA accounts increased by 39%.

Significant diversion of HST revenues coupled with declining oil prices have been dire for MTCA. Consequently, budget shortfalls of millions of dollars have prompted budget cuts which have inhibited cleanup capabilities. Legislative diversion of HST funds clearly demonstrates a deviation from MTCA’s original intent to “to raise sufficient funds to clean up all hazardous waste sites” . The reallocation of HST funds from cleanup to other purposes has become MTCA’s myth. Thus, MTCA’s ability to clean sites has been degraded.

Remedial Purgatory

It does appear that Goose Lake may be one of many sites that “have been languishing for years because money has been diverted from the cleanup program”. Little information is available on why Goose Lake’s cleanup has stalled. However, when researching for this paper I corresponded with ECY site manager Connie Groven. I asked about Goose Lake’s current status. Groven attributed the lack of progress on the site Feasibility Study to “staffing and workload issues over the past few years”. She is likely referring to Goose Lake’s most recent period of inactivity.

From 2018-2024, ECY only managed to start the Feasibility Study. This period coincides with ECY’s era of “prioritizing the delay of cleanup projects” and goals to “use limited funds wisely” following 2014-2018 MTCA budget shortfalls. While I cannot say for sure that Goose Lake’s cleanup process has been hindered by HST reallocation, several signs point to yes. Other factors such as Hall Equities Group pulling out of cleanup agreements has certainly stalled progress. A lack of funding also appears to have limited the ability of ECY to facilitate the process.

Defunding MTCA neglects communities by exposing them to toxic sites for prolonged periods of time. Goose Lake was ranked at the second highest level of human and ecological exposure risk in 1998. In this hazard assessment, Goose Lake was ranked at maximum risk levels for surface and ground water release of Arsenic, Chromium, and Mercury. Yet, Goose Lake and its surrounding wetlands are located within the class I extremely critical aquifer recharge areas . This means that Goose Lake’s toxic water could be leeching directly into the most crucial area for Shelton’s drinking water supply.

Goose Lake is also a popular recreational destination in Shelton. The area hosted upwards of 300 visitors in 2023 for the Shelton Valley Fun Run, a dirt bike race hosted by Puget Sound Enduro Riders Motor Club. I have also witnessed several people fishing and swimming in the lake, even finding a discarded children’s swimming mask, shown in figure 3. I found this kid’s mask on the shore of a lake that contains 14 times as much hazardous waste as America's most notorious toxic canal. Goose Lake’s delayed cleanup may pose dangers to the people enjoying the recreational opportunities of the site, such as the child who left their goggles behind.

Children's swimming mask on the shore of Goose Lake.

Still Waiting

Originally, MTCA aimed to fund the cleanup of all hazardous waste sites. Then, their principles shifted. Funds were reallocated away from the MTCA account during the Great Recession. Millions of dollars were siphoned out of MTCA “to cover non-cleanup purposes”. However, the myth of funding cleanup remained and obscured MTCA’s increasing budget shortfalls. This shift to prioritize delay demonstrates how the degradation of program principles has inhibited cleanup activities. I’m still waiting for my favorite Superfund site’s cleanup.

Maisie Gill is an Urban Planning and Sustainable Development student who is curious about how land use legacies effect contemporary life.

This paper was written for UEPP 355: Environmental Law and Policy at Western Washington University and published with permission from both the author and professor.