Attack of the Wasting Disease

Something is killing sea stars by the billions, and researchers have yet to understand why.

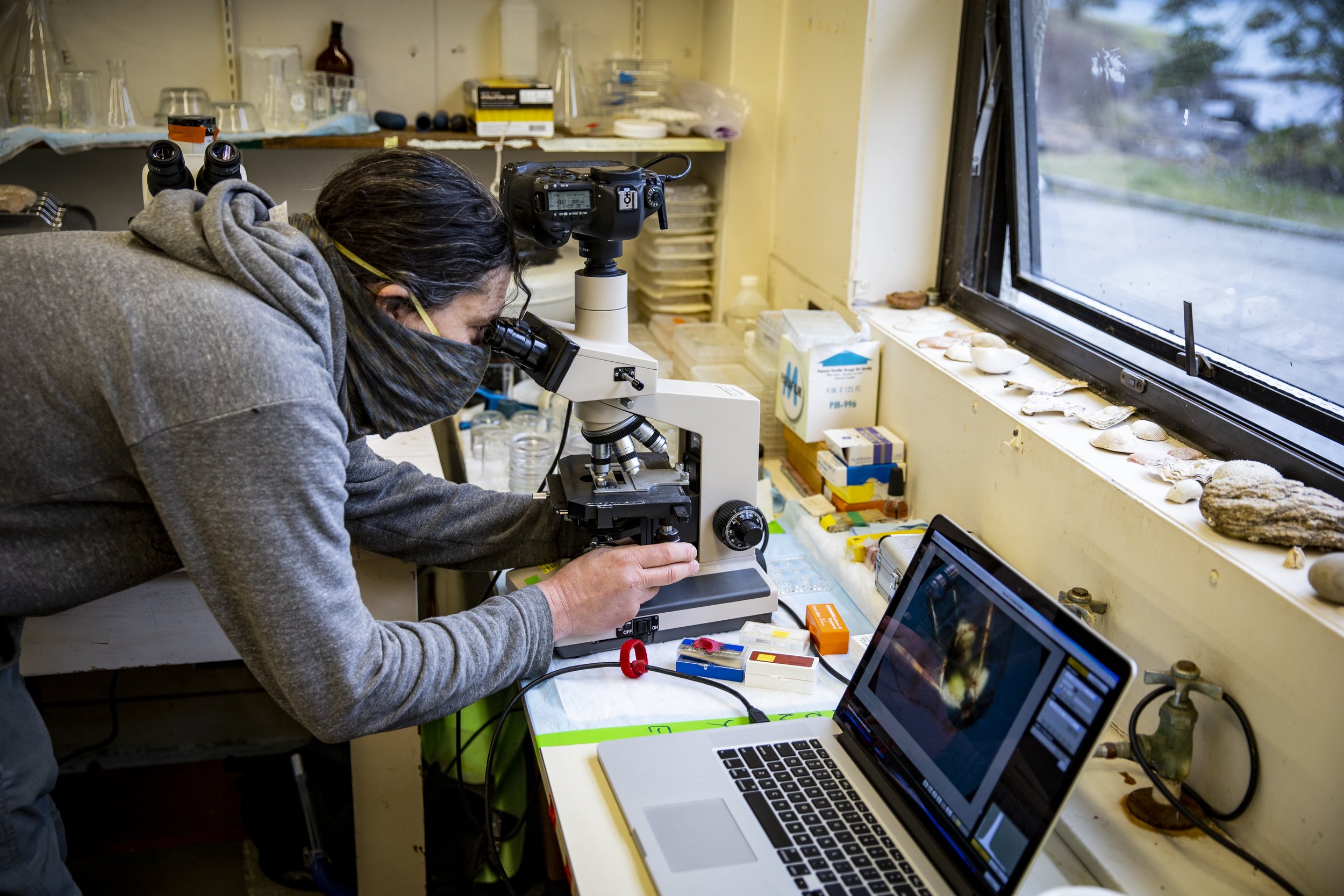

The underside of an adult sunflower sea star feeding on mussels. More than two dozen adult sunflower stars make up a breeding colony at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories on San Juan Island, where researchers are rearing sea stars in captivity in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy. The species was recently listed as critically endangered, the first such listing for any starfish species worldwide. // Dennis Wise - University of Washington

Story by Micah Abdul Kruser

December 5, 2023

Within the rocky shoals of tidal zones, amidst mussels and swaying kelp, sea stars are trying desperately to hang on. Some have lesions on their bodies, are missing arms or are just squishy, flesh-like goo. Sea star wasting syndrome has become a leading killer of sea stars along the Pacific coast.

This disease has led to the death of billions of sea stars. Over twenty species have experienced a decline. Numbers of the local sunflower sea star have dropped by 90% as of 2021 according to research conducted by the University of Washington.

Sunflower sea stars, or Pycnopodia helianthoides, are considered a keystone species, meaning that they have a big impact on their ecosystem, even if their population size is relatively small. The diet of this animal consists of purple urchins, along with clams and other small sea critters. Without the multiple armed predators—some as large as a bike wheel—urchin populations can go out of control and overgraze kelp forests.

Because of the decrease in sea otter populations, and now sunflower sea stars, some kelp forests along the west coast have become what researchers call urchin barrens. Instead of a healthy kelp grove, rows of pointy urchins roam a desolate and barren landscape.

Kelp forests give shelter to various ocean species, making them one of the most diverse habitats in the ocean. The loss of this important habitat is a worry for Heather Coletti, a marine ecologist with the National Parks Service who conducts monitoring of intertidal zones in Alaska.

“The value of long-term monitoring allows us to assess impacts of these perturbations to the communities and without it, we wouldn't know what was going on or what it should look like,” Coletti said.

The most recent epidemic was first spotted in sea stars in 2013 and research has since provided details on just how fast-moving and devastating this disease can be. What researchers can’t pin down, however, is its cause.

Sea star wasting disease may be exacerbated by warming seas. A giant patch of warmer ocean water, nicknamed “The Blob”, is 4 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the surrounding water. This patch moved into the Pacific Ocean in 2013 and may have amplified the effects of the wasting syndrome.

It's difficult to pin down a cause for the disease when healthy sea stars are so rare to find, according to Morgan Eisenlord, an instructor at Western Washington University and a researcher at Shannon Point Marine Labs.

Dive teams at Shannon Point collected what were thought to be healthy sea stars and brought them into their research aquarium. Mere months later, the sea stars showed signs of the wasting disease.

“It’s very hard to continue that work when you don’t have animals you can confirm are uninfected, so it really limited what could be done,” Eisenlord said.

Other possible causes of the wasting syndrome may be environmental changes. Increased pollution, water temperature changes and pH shifts have all been present in areas with the disease. No data can pin down a direct correlation, however. Sunflower star populations also range from intertidal to subtidal zones. These zones face a constant flux of water and changes in temperature due to tides. This makes it hard to pinpoint what variables to measure, according to Eisenlord.

“It really seems very highly likely that the underlying cause is infectious disease, but we can’t confirm exactly what that is,” Eisenlord said.

The only way researchers have been able to aid individual sea stars afflicted with the disease is by taking infected hosts out of the sea and placing them in aquariums. There, sea star patients receive an array of treatments, from iodine soaks to antibiotics. Even with intensive treatment, the sea star survival rate is only around 30%, according to Erin Merklein, volunteer coordinator at the Padilla Bay Reserve.

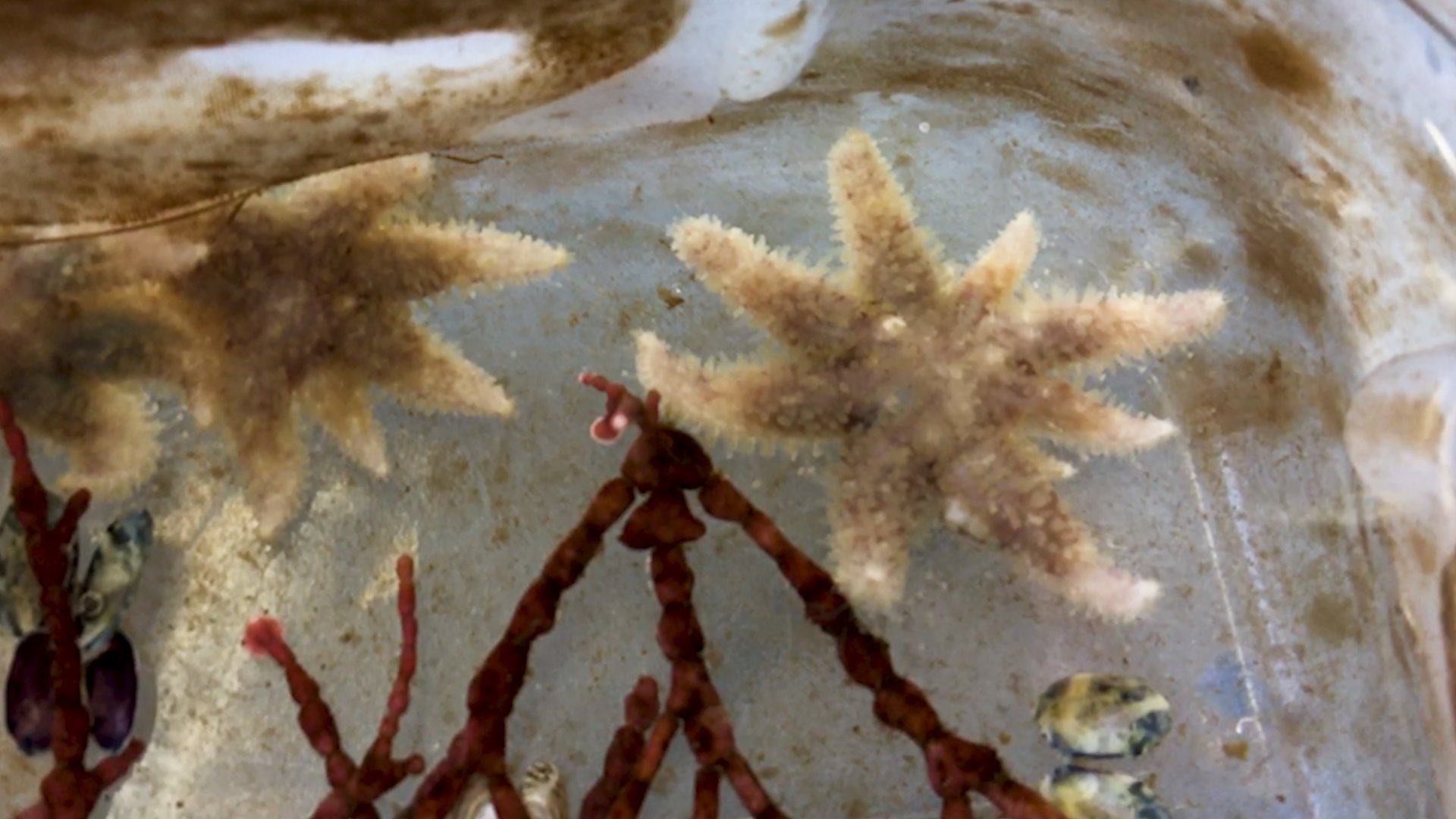

Other researchers at Friday Harbor Labs are raising young sunflower sea stars which can be as small as poppy seeds. The oldest ones they currently house are four years old, although the team thinks the stars’ full-grown size may not be reached until seven years old. No one knows how long sunflower stars can live, although some have been taken from the wild at an unknown age and held in captivity for decades. After maturity, the stars can shrink and grow depending on food availability.

Sunflower sea star larvae, born in mid-January, seen under a microscope. The dark oval shapes are stomachs. The sunflower sea star captive breeding program is a partnership between University of Washington and The Nature Conservancy. // Dennis Wise - University of Washington

“We’re basically raising a tiger. We gotta come up with a lot of food for them. They’re ravenous,” Jason Hodin, a senior research scientist at Friday Harbor Labs, said.

Both adolescent and adult sea stars are opportunistic predators and have a huge impact on their ecosystem, according to Hodin. Without these voracious eaters, huge disruptions have occurred in the food web, including the rise in mussel populations and the decline in kelp forests.

Hodin’s team of researchers has discovered additional signs of sea star wasting syndrome in sunflower sea stars. The progression of the disease is grim: the distortion of the sea star's body, followed by the curling of arms, lack of appetite, lesions on the body, the dropping of arms and then death. The team at Friday Harbor found that even before these symptoms begin, a sunflower star begins to twist its body. If this warning sign is caught by researchers early, the star has a much better chance of survival, according to Hodin.

Prior work studying the sea star population allows researchers to estimate the decimation caused by this disease. No one hopes for a species to be listed as endangered, according to Coletti. However, this may be the next step to preserve sea star populations. Placing sea stars on the endangered species list would mean more funding for research on wasting disease and mitigating the impacts of water pollution and dredging.

But placing a species on the list is easier said than done.

“Even if we do ESA [Endangered Species Act] list the species, Canada can just say ‘Eh, whatever’,” Hodin said. “NOAA has no jurisdiction in Canadian waters.”

Eisenlord emphasized that adding sunflower stars to the endangered species list would increase public awareness and hopefully support for the species’ protection.

“There really is no place that they [sunflower stars] are doing well,” Eisenlord said. “We really are at risk of losing them completely.”

Micah Abdul Kruser is a senior GIS student exploring and educating on environmental issues across our geography.