Whatcom’s Goop Problem

Invasive tunicates are gumming up the works of local aquaculture.

Story and Photos by Jack Gates

March 18, 2025

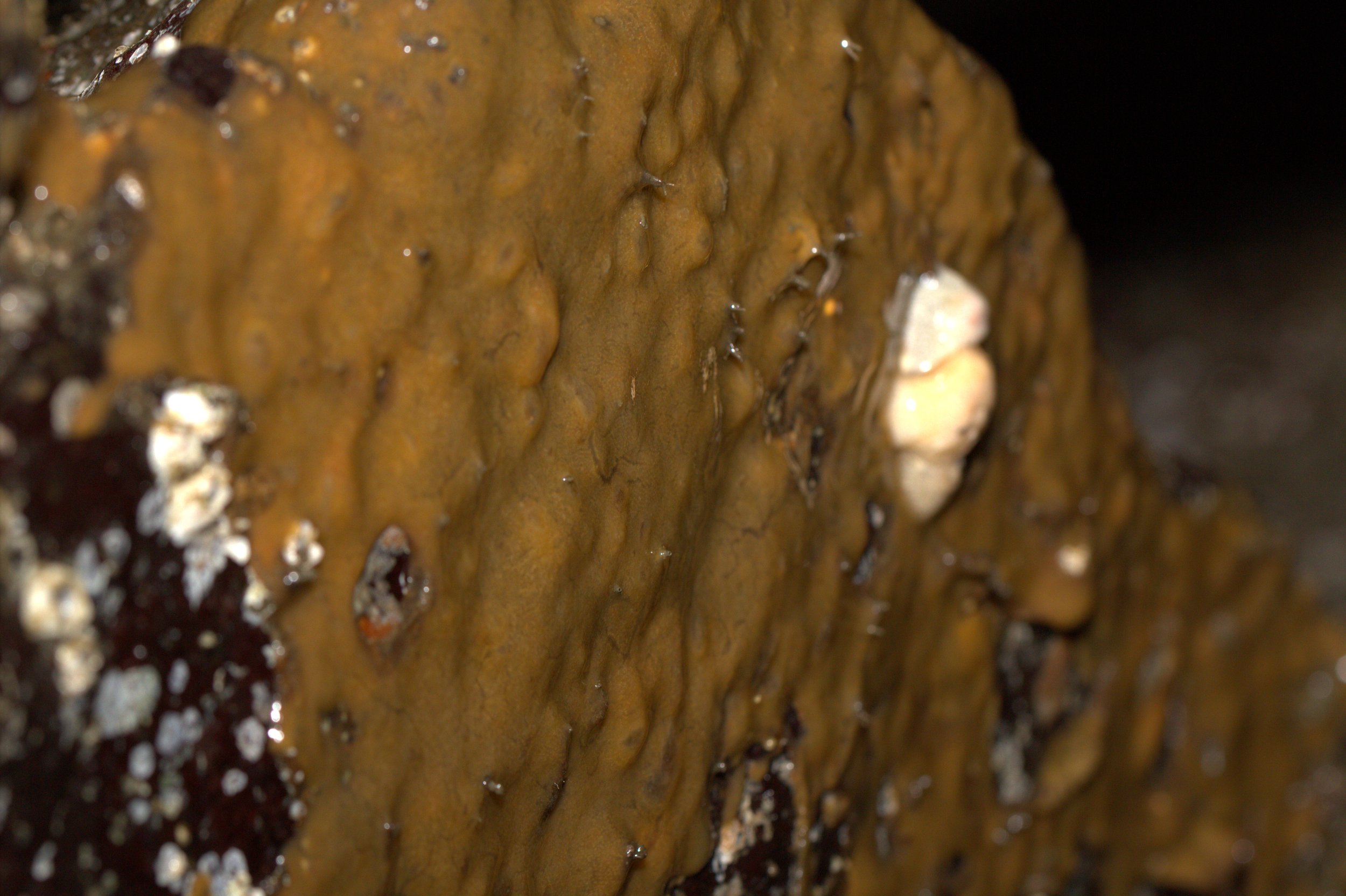

Tunicates, looking like slimy globs when removed from the water, overgrow mussels and other stationary creatures. This clump of mussels and tunicates was seen in Blaine Harbor in March 2025.

A beachgoer flips over a rock at Larrabee State Park to reveal an underside blanketed in a shiny, orange mat. This globby animal is an invasive tunicate, Didemnum vexillum. These vexing globs overgrow other marine creatures throughout Pacific Northwest waters and threaten aquaculture.

Tunicates are invertebrate animals that feed voraciously by pumping water through their bodies to capture bits of food. Colonial tunicates were first discovered in Washington in 1998, and are suspected to have been introduced on imported oyster seed. Other species of invasive tunicate likely arrived in Washington by hitchhiking on ships.

“[Tunicates are] able to filter and capture at high rates and efficiently, more so than shellfish,” Samuel Chan, an aquatic invasive species expert and member of the Oregon Invasive Species Council said. “Tunicates have thousands of pumps… that’s how they compete with other organisms, is by sheer mass and efficiency.”

According to Chan, because barnacles and shellfish tend to be stationary they can’t escape from being crusted over by tunicates.

In addition to their aggressive growth and feeding, colonial tunicates have a repertoire of ways to multiply, making them adept at dispersing and infesting new areas.

“A tunicate can reproduce by fragmenting itself into small pieces, or it can do what we call budding, where it creates essentially a clone of itself,” Chan said. “When they reproduce sexually, there is a microscopic planktonic phase–we call them tadpoles–that swim. And, when swimming, they’re able to then find a new home, attach, and then start growing.”

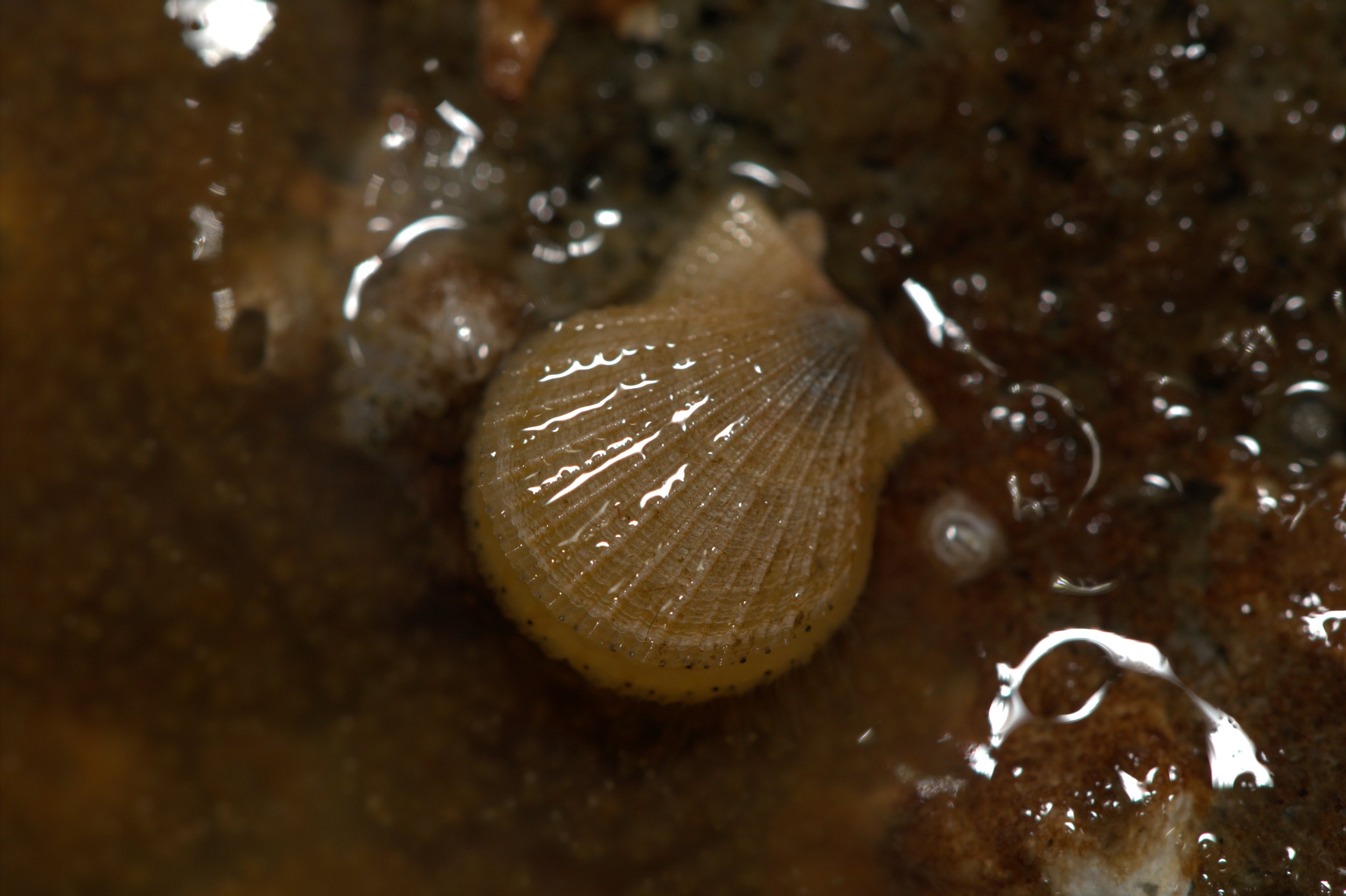

Didemnum vexillum can be found at low tides on Whatcom County’s beaches, such as Larrabee State Park. Here, it was observed spreading over barnacles. Other creatures, including a scallop and another species of colonial tunicate, were surrounded by the colony.

Ciona growing on the side of a floating dock at Blaine Harbor in March 2025. These were seen in abundance in protected areas of the harbor, growing alongside algae, tubeworms, and anemones.

Didemnum vexillum is a colonial tunicate, meaning each clump of orange consists of many individual animals.

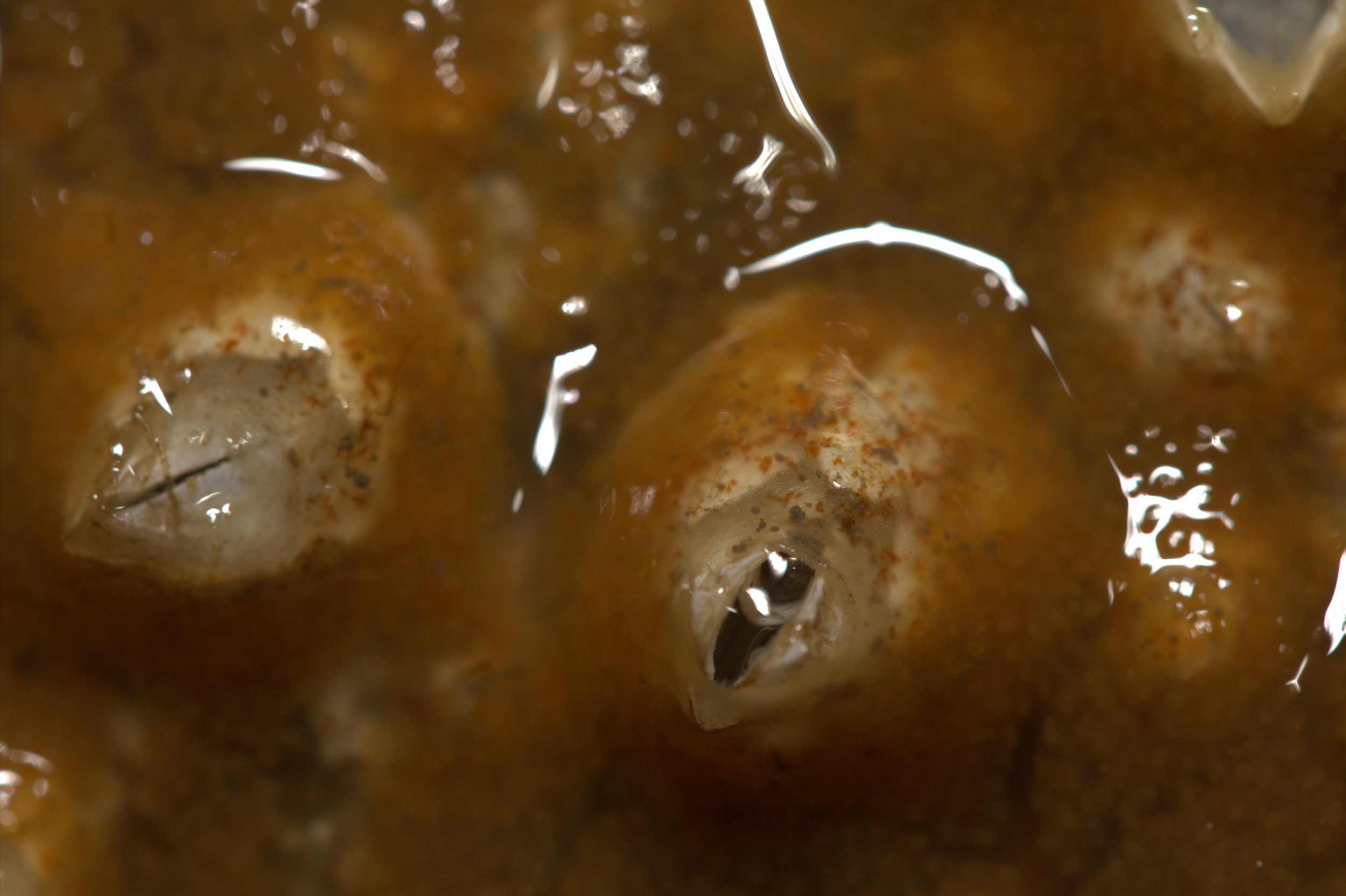

Didemnum vexillum isn’t the only invasive tunicate in Washington. Other species of concern include Ciona savignyi, which resembles a glass vase, and the club tunicate, Styela clava, which resembles a warty club.

Ciona savignyi and Styela clava are solitary rather than colonial, each vase-like creature is a single individual. Unlike colonial tunicates which have many siphons pumping water at once, solitary tunicates have only one siphon. Still, these species outcompete and smother other stationary creatures.

Styela clava attached to the side of a boat launch in Blaine Harbor in March 2025.

On top of the ecological impacts, invasive tunicates pose a threat to aquaculture and smother farmed shellfish.

Whether it’s the European green crab or invasive tunicates, oyster growers say that invasive species have a ten percent impact on their crops. Together, invasive species have additive effects on aquaculture, Chan said.

Invasive tunicates may have the potential to harm Dungeness crab fisheries, as well. As Didemnum vexillum spreads, it could diminish the Dungeness crab’s food sources.

A large clump of mussels growing on a boat line at Blaine Harbor was covered by Ciona and Styela clava in March, 2025. These species were abundant on floating docks throughout the harbor, only inches away from docked boats.

“Dungeness crabs are feeding on many of the organisms that could be impacted by Didemnum,” said Chan.

A large clump of mussels growing on a boat line at Blaine Harbor was covered by Ciona and Styela clava in March, 2025. These species were abundant on floating docks throughout the harbor, only inches away from docked boats.

Currently, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife has no management actions that are specific to invasive tunicates.

“We don’t have dedicated funding for invasive tunicates…[the legislature] gives funding for other species, some of the highest priority,” Jesse Schultz, an invasive species biologist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife said.

However, tunicates are regulated by management actions that apply to all aquatic invasive species in the state. Management is primarily through a state law that requires aquatic structures to be cleaned and drained before being transported over roads. This applies to any property in the water, including boats, docks and barges, preventing organic material from being transferred between bodies of water. These regulations could prevent new infestations of invasive tunicates.

“We [won't] be able to manage every single aquatic invasive species in the state…the better process is focusing on preventing the spread of any invasive species,” Schultz said. “ That’s mandatory decontamination of equipment before it goes into another [body of water]. That’s not specifically for tunicates, but it will reduce the spread greatly if you conduct these decontamination measures.”

While there is management in place to lessen the spread of tunicates, eradicating them from an area where they are already established is less simple. Tunicates must be manually removed from boats in harbors by divers, according to Schultz.

“It’s very difficult to treat tunicates,” Chan said. “[If] they’re embedded in a jetty, you just can’t treat a jetty wall well enough to kill all the organisms, or pump enough chemicals in there to not impact something else.”

Invasive tunicates have established themselves in Washington’s waters. While they are less of a priority than other invasive species like the European green crab, these tunicates have the potential to impact our marine food sources and ecosystems.

“Because they’re more tolerant, they’re going to be able to live more in our changing marinescape,” Chan said, “which means it might affect our fisheries and the health of these waters.

A marina in Blaine, home to an abundance of invasive tunicates.